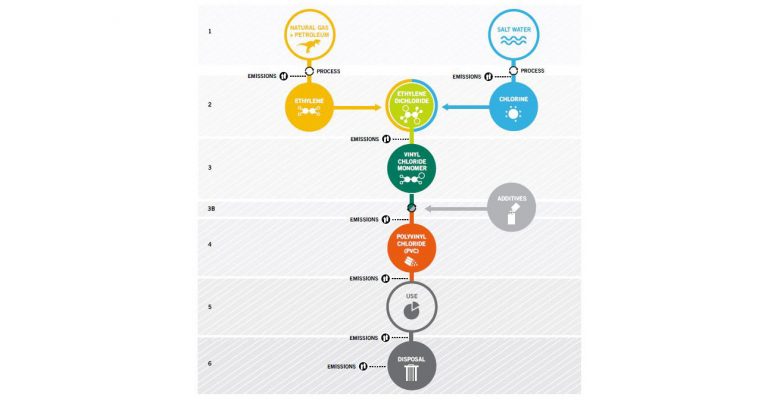

PVC is a popular, highly versatile, low-cost, durable material used in a wide variety of building product applications. However, PVC is unique within the broad spectrum of plastics because it is a chlorinated plastic. Its chlorinated chemistry is responsible for a range of environmental and human health hazards: from the beginning of its lifecycle where the vinyl chloride monomer is a known human carcinogen; to the release of dioxin, another human carcinogen, when PVC is manufactured; and when PVC burns in accidental building and landfill fires, in jobsite burn barrels, as well as in incinerators. PVC-related wastes constitute four of the first 12 substances targeted for international action by the 2001 Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs).

An extensive range of additives is needed to improve vinyl’s versatility and offset the limitations of the plastic. These include lead-based stabilizers and toxic plasticizers, called phthalates, to make it suitable for flexible applications such as flooring, wall covering, and membrane roofing. Additives are not chemically bound to the plastic, and have been documented to migrate out of vinyl products and into household dust, exposing occupants.

In recent years, as data on potential health hazards have emerged and the market has moved to alternative products, PVC product manufacturers have been replacing many of the toxic additives. The reformulated products are the subject of a new rebranding campaign in the vinyl industry; “clean-vinyl” and “bio-vinyl” are two examples of the trade names at the forefront of this campaign to position vinyl as a breakthrough and advanced green product. While improved by excluding problematic additives, these reformulations have not—and cannot—address the lifecycle hazards tied to PVC’s intrinsic chlorinated chemistry.

Further, recycling rates for PVC are very low, but when it does get recycled, workers and the communities surrounding recycling facilities can be exposed to its additives. Once incorporated into the manufacture of new vinyl products, the use of recycled PVC becomes a pathway for the introduction of serious legacy contaminants from prior vinyl formulations into these new vinyl products—including many of the very additives the new formulations have been designed to avoid.

Influential materials rating systems, including the Living Building Challenge building certification and Cradle to Cradle product certifications recommend avoiding PVC. Influential building owners such as Kaiser Permanente and Google have adopted PVC avoidance policies. Perkins+Will, an international architecture practice with about 1,000 architects, included PVC in its Precautionary List as a substance for which to seek alternatives.

Consideration of the current state of PVC manufacturing practices and use of recycled content supports the position that PVC continues to pose hazards to human health. Avoiding PVC in building material choices is nearly always preferable from an overall human health and environmental perspective, recognizing that there may (or may not) be tradeoffs with other environmental attributes depending upon which material is selected.

Click here to read the full paper.